IPFS Phishing Attacks

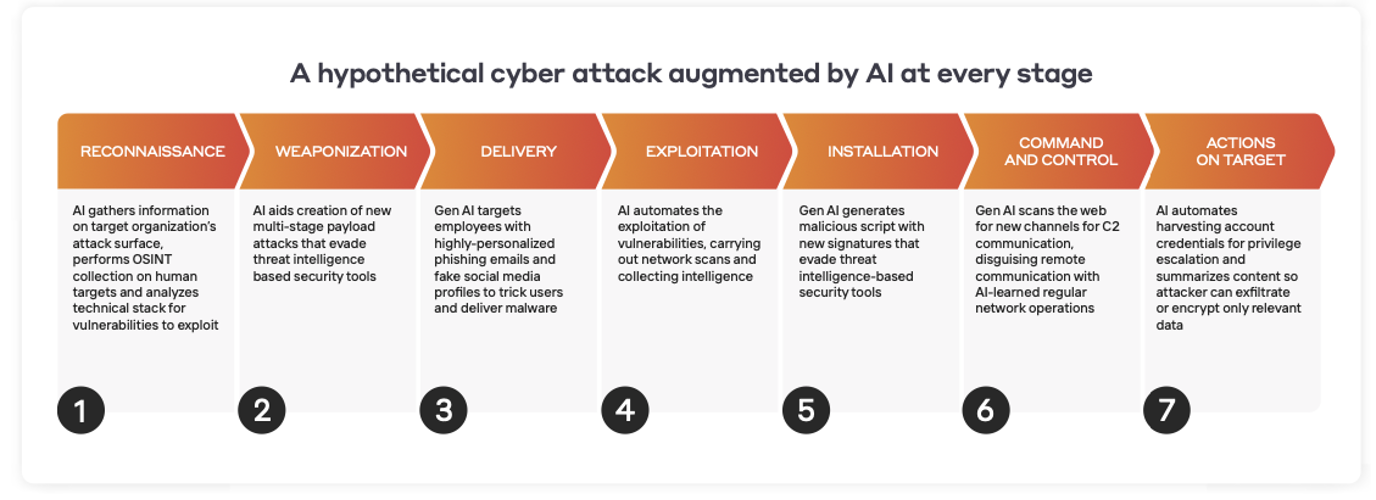

Phishing attacks continue to be one of the most common methods of infiltration utilized by threat actors and they represent a significant threat to an organization’s digital estate. As phishing campaigns typically leverage social engineering methods to evade security tools and manipulate users into following links, downloading files, or divulging confidential information. It is a relatively low effort but high-yield type of cyber-attack.

That said, in recent years security teams have become increasingly savvy to these efforts. Attackers are having to adapt and come up with novel ways to carry out their phishing campaigns. Recently, Darktrace has observed a rise in phishing attacks attempting to abuse the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) in campaigns that are able to dynamically adapt depending on the target, making it extremely difficult for security vendors to detect and investigate.

What is a IPFS?

IPFS is a file storage protocol a peer-to-peer (P2P) network used for storing and sharing resources in a distributed file system [1]. It is also a file storage system similar in nature to other centralized file storage services like Dropbox and Google Drive.

File storage systems, like IPFS, are often abused by malicious actors, as they allow attackers to easily host their own content without maintaining infrastructure themselves. However, as these file storage systems often have legitimate usages, blocking everything related to file storages may cause unwanted problems and affect normal business operations. Thus, the challenge lies in differentiating between legitimate and malicious usage.

While centralized, web-based file storage services use a Client-Server model and typically deliver files over HTTP, IPFS uses a Peer-to-Peer model for storing and sharing files, as shown in Figure 1.

To verify the authenticity and integrity of files, IPFS utilizes cryptographic hashes.

A cryptographic hash value is generated using a file’s content upon upload to IPFS. This is used to generate the Content Identifier (CID). IPFS uses Content Addressing as opposed to Location Addressing, and this CID is used to point to a resource in IPFS [4].

When a computer running IPFS requires a particular file, it asks the connected peers if they have the file with a specific hash. If a peer has the file with the matching hash, it will provide it to the requesting computer [1][6].

Taking down content on IPFS is much more difficult compared to centralized file storage hosts, as content is stored on several nodes without a centralized entity, as shown in Figure 2. To take down content from IPFS, it must be removed from all the nodes. Thus, IPFS is prone to being abused for malicious purposes.

The domains used in these IPFS phishing links are gateways that enable an HTTPS URL to access resources within the distributed IPFS file system.

There are two types of IPFS links, the Path Gateway and Subdomain Gateway [1].

Path Gateways have a fixed domain/host and identifies the IPFS resource through a resource-identifying string in the path. The Path Gateway has the following structure:

• https://<gateway-host>.tld/ipfs/<CID>/path/to/resource

• https://<gateway-host>.tld/ipns/<dnslink/ipnsid>/path/to/resource

On the other hand, Subdomain Gateways have a resource-identifying string in the subdomain. Subdomain Gateways have the following structure:

• https://<cidv1b32>.ipfs.<gateway-host>.tld/path/to/resource

One gateway domain serves the same role as any other, which means attackers can easily change the gateways that are used.

Thus, these link domains involved in these attacks can be much more variable than the ones in traditional file storage attacks, where a centralized service with a single domain is used (e.g., Dropbox, Google Docs), making detecting the malicious use of IPFS extremely challenging for traditional security vendors. Through its anomaly-based approach to threat detection, Darktrace/Email™ is consistently able to identify such tactics and respond to them, preventing malicious actors from abusing file storage systems life IPFS.

IPFS Campaign Details

In several recent examples of IPFS abuse that Darktrace detected on a customer’s network, the apparent end goal was to harvest user credentials. Stolen credentials can be exploited by threat actors to further their attacks on organizations by escalating their privileges within the network, or even sold on the dark web.

Darktrace detected multiple IPFS links sent in malicious emails that contained the victim’s email address. Based on the domain in this email address, users would then be redirected to a fake login page that uses their organizations’ webpage visuals and branding to convince targets to enter their login details, unknowingly compromising their accounts in the process.

These IPFS credential harvesting sites use various techniques to evade detection the detection of traditional security tools and prevent further analysis, such as obfuscation by Percent Encoding and Base64 Encoding the code.

There are also other mechanisms put into place to hinder investigation by security teams. For example, some IPFS credential harvester sites investigated by Darktrace did not allow right clicking and certain keystrokes, as a means to make post-attack analysis more difficult.

In the campaign highlighted in this blog, the following IPFS link was observed:

hxxps://ipfs[.]io/ipfs/QmfDDxLWoLiqFURX6dUZcsHxVBP1ZnM21H5jXGs1ffNxtP?filename=at ob.html#<EmailAddress>

This uses a Path Gateway, as it identifies the IPFS resource through a resource-identifying string in the path. The CID is QmfDDxLWoLiqFURX6dUZcsHxVBP1ZnM21H5jXGs1ffNxtP in this case.

It makes a GET request to image[.]thum[.]io and logo[.]clearbit[.]com as shown in Figure 5. The image[.]thum[.]io is a Free Website Screenshot Generator, that provides real-time screenshot of websites [2]. The logo[.]clearbit[.]com is used to lookup company logos using the domain [3]. These visuals are integrated into the credential harvester site. Figure 6 shows the domain name being extracted from the victim’s email address and used to obtain the visuals.

The code reveals the credential POST endpoint as shown in Figure 16. When credentials are submitted, it makes a POST request to this endpoint as shown in Figure 7.

From the IPFS link alone, it is difficult to determine whether it leads to a malicious endpoint, however Darktrace has consistently identified emails containing these IPFS credential harvesting links as phishing attempts.

Darktrace Coverage

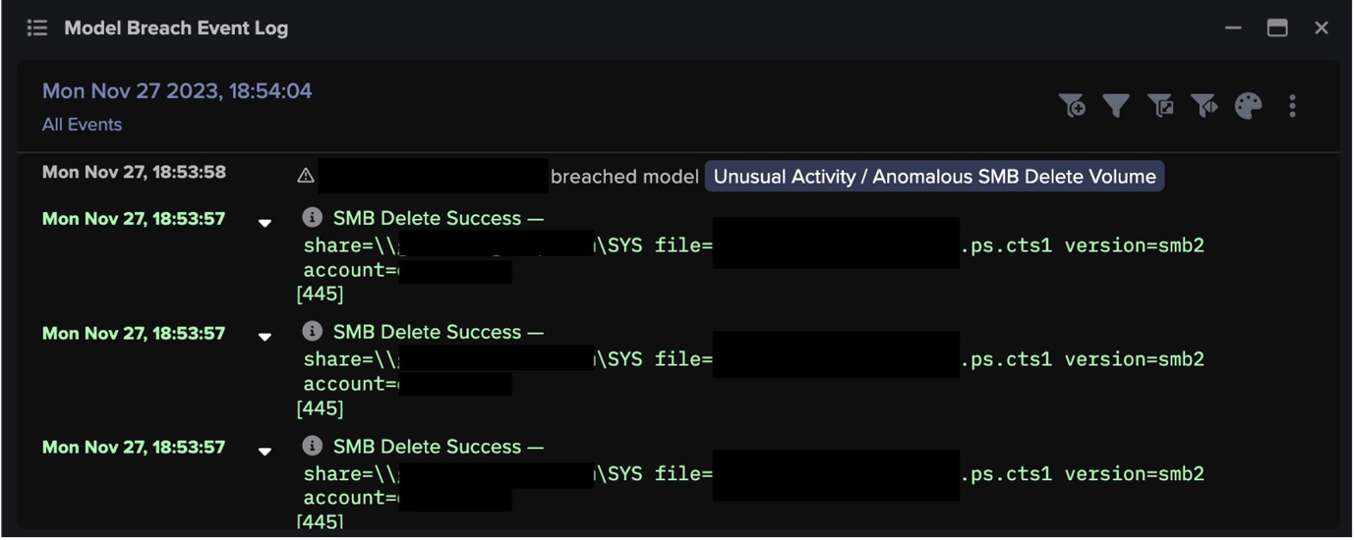

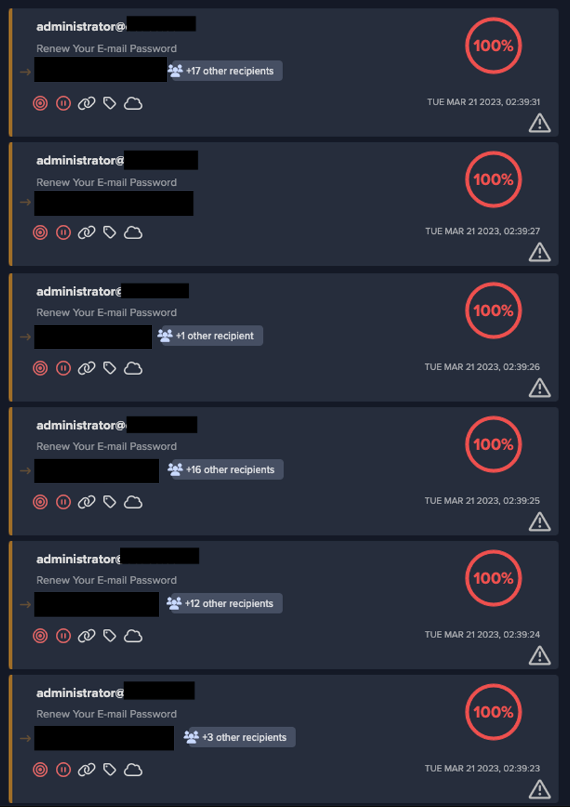

During one case of IPFS abuse detected by Darktrace in March 2023, a threat actor sent malicious emails with the subject “Renew Your E-mail Password” to 55 different recipients at. The sender appeared to be the organization’s administrator and used their internal domain.

However, Darktrace recognized that the email did not pass Sender Policy Framework (SPF), and therefore it could not be validated as being sent from the organization’s domain. Darktrace also detected that the email contained a link to “ipfs.io, the official IPFS gateway. This was identified as a spoofing and phishing attempt by Darktrace/Email.

Following the successful identification of the malicious emails, Darktrace RESPOND™ took immediate autonomous action to prevent them from leading to potentially damaging network compromise. For email-based threats, Darktrace RESPOND is able to carry out numerous actions to stop malicious emails and reduce the risk of compromise. In response to this specific incident, RESPOND took multiple preventative actions (as seen in Figure 11), including include lock link, an action that prevents access to URLs deemed as suspicious, send to junk, an action that automatically places emails in the recipient’s junk folder, and hold message, the most severe RESPOND action that prevents malicious emails from reaching the recipients inbox at all.

Further investigation revealed that the IPFS link contained the recipients’ email address, and when clicked led to a credential harvester that utilized the same visuals and branding as the customer’s website.

Concluding Thoughts

Ultimately, despite the various tactics employed threat actors to evade the detection of traditional security tools, Darktrace was able to successfully detect and mitigate these often very fruitful phishing attacks that attempted to abuse the IPFS file storage system.

As file storage platforms like IPFS do have legitimate business uses, blocking traffic related to file storage is likely to negatively impact the day-to-day operations of an organization. The challenge security teams face is to differentiate between malicious and legitimate uses of such services, and only act on malicious cases. As such, it is more important than ever for organizations to have an effective anomaly detection tool in place that is able to identify emerging threats without relying on rules, signatures or previously observed indicators of compromise (IoC).

By leveraging its Self-Learning AI, Darktrace understands what represents expected activity on customer networks and can recognize subtle deviations from expected behavior, that may be indicative of compromise. Then, using its autonomous response capabilities, Darktrace RESPOND is able to instantly and autonomously take action against emerging threats to stop them at the earliest possible stage.

Credit to Ben Atkins, Senior Model Developer for their contribution to this blog.

Appendices

Example IOCs

Type: URL

IOC: hxxps://ipfs[.]io/ipfs/QmfDDxLWoLi qFURX6dUZcsHxVBP1ZnM21H5jXGs

1ffNxtP?filename=atob.html#<Email Address>

Description: Path Gateway link

Type: URL

IOC: hxxps://bafybeibisyerwlu46re6rxrfw doo2ubvucw7yu6zjcfjmn7rqbwcix2 mku.ipfs[.]dweb.link/webn cpmk.htm?bafybeigh77sqswniy74nzyklybstfpkxhsqhpf3qt26nwnh4wf2vv gbdaybafybeigh77sqswniy74nzyklybstfpkxhsqhpf3qt26nwnh4wf2vvgbda y#<EmailAddress>

Description: Subdomain Gateway link

Relevant Darktrace DETECT Models

• Spoof / Internal Domain from Unexpected Source + New Unknown Link

• Link / High Risk Link + Low Sender Association

• Link / New Correspondent Classified Link

• Link / Watched Link Type

• Proximity / Phishing + New activity

• Proximity / Phishing + New Address Known Domain

• Spoof / Internal Domain from Unexpected Source + High Risk Link

References

[4] https://filebase.com/blog/ipfs-content-addressing-explained/

[5] https://www.trustwave.com/en-us/resources/blogs/spiderlabs-blog/the-attack-of-the-chameleon-phishing-page/

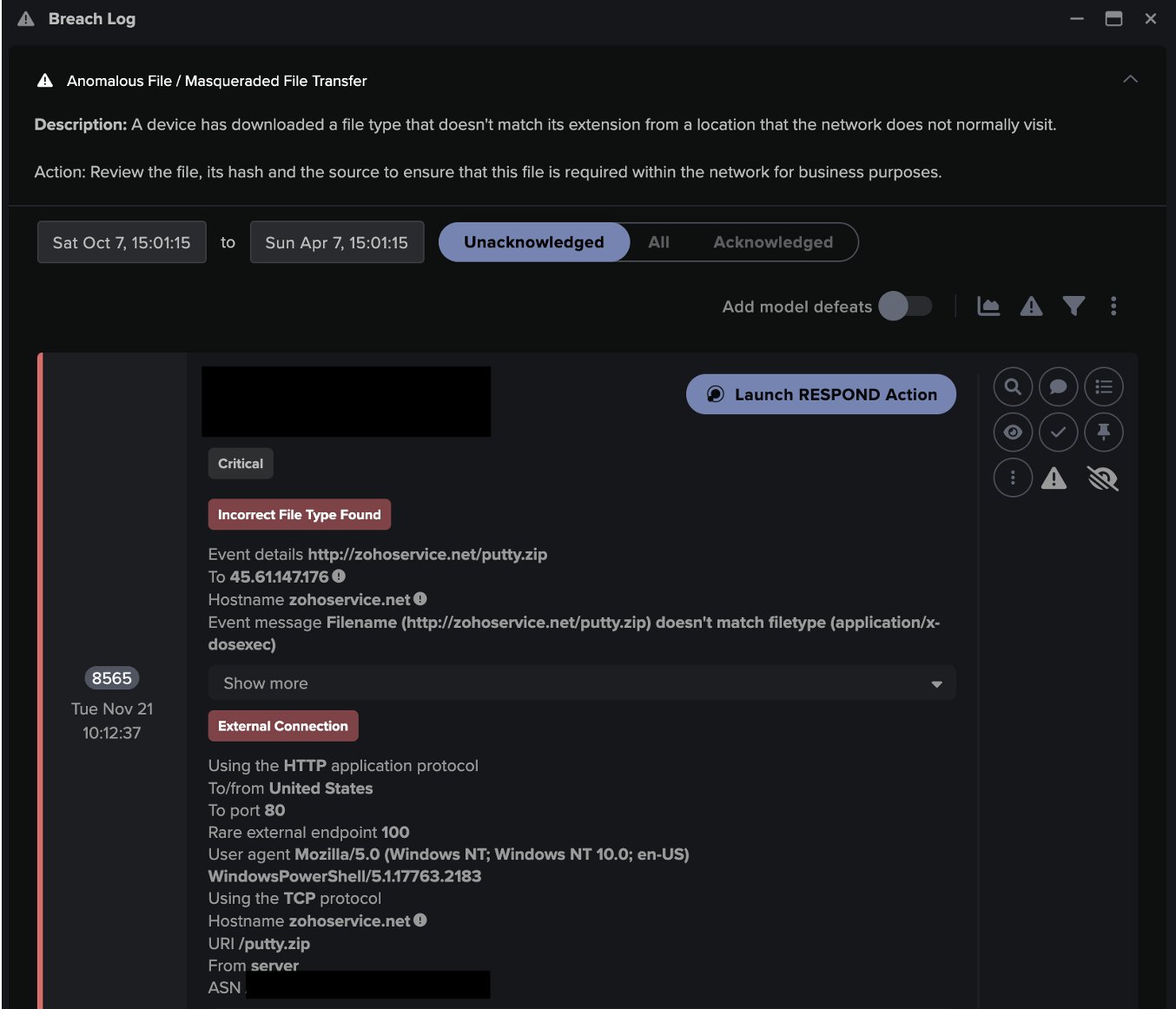

![Cyber AI Analyst Incident Log showing the offending device making over 1,000 connections to the suspicious hostname “zohoservice[.]net” over port 8383, within a specific period.](https://assets-global.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/662971c1cf09890fd46729a1_Screenshot%202024-04-24%20at%201.55.10%20PM.png)