In June 2022, Darktrace observed a surge in Qakbot infections across its client base. The detected Qakbot infections, which in some cases led to the delivery of secondary payloads such as Cobalt Strike and Dark VNC, were initiated through novel delivery methods birthed from Microsoft’s default blocking of XL4 and VBA macros in early 2022 [1]/[2]/[3]/[4] and from the public disclosure in May 2022 [5] of the critical Follina vulnerability (CVE-2022-30190) in Microsoft Support Diagnostic Tool (MSDT). Despite the changes made to Qakbot’s delivery methods, Qakbot infections still inevitably resulted in unusual patterns of network activity. In this blog, we will provide details of these network activities, along with Darktrace/Network’s coverage of them.

Qakbot Background

Qakbot emerged in 2007 as a banking trojan designed to steal sensitive data such as banking credentials. Since then, Qakbot has developed into a highly modular triple-threat powerhouse used to not only steal information, but to also drop malicious payloads and to serve as a backdoor. The malware is also versatile, with its delivery methods regularly changing in response to the changing threat landscape.

Threat actors deliver Qakbot through email-based delivery methods. In the first half of 2022, Microsoft started rolling out versions of Office which block XL4 and VBA macros by default. Prior to this change, Qakbot email campaigns typically consisted in the spreading of deceitful emails with Office attachments containing malicious macros. Opening these attachments and then enabling the macros within them would lead users’ devices to install Qakbot.

Actors who deliver Qakbot onto users’ devices may either sell their access to other actors, or they may leverage Qakbot’s capabilities to pursue their own objectives [6]. A common objective of actors that use Qakbot is to drop Cobalt Strike beacons onto infected systems. Actors will then leverage the interactive access provided by Cobalt Strike to conduct extensive reconnaissance and lateral movement activities in preparation for widespread ransomware deployment. Qakbot’s close ties to ransomware activity, along with its modularity and versatility, make the malware a significant threat to organisations’ digital environments.

Activity Details and Qakbot Delivery Methods

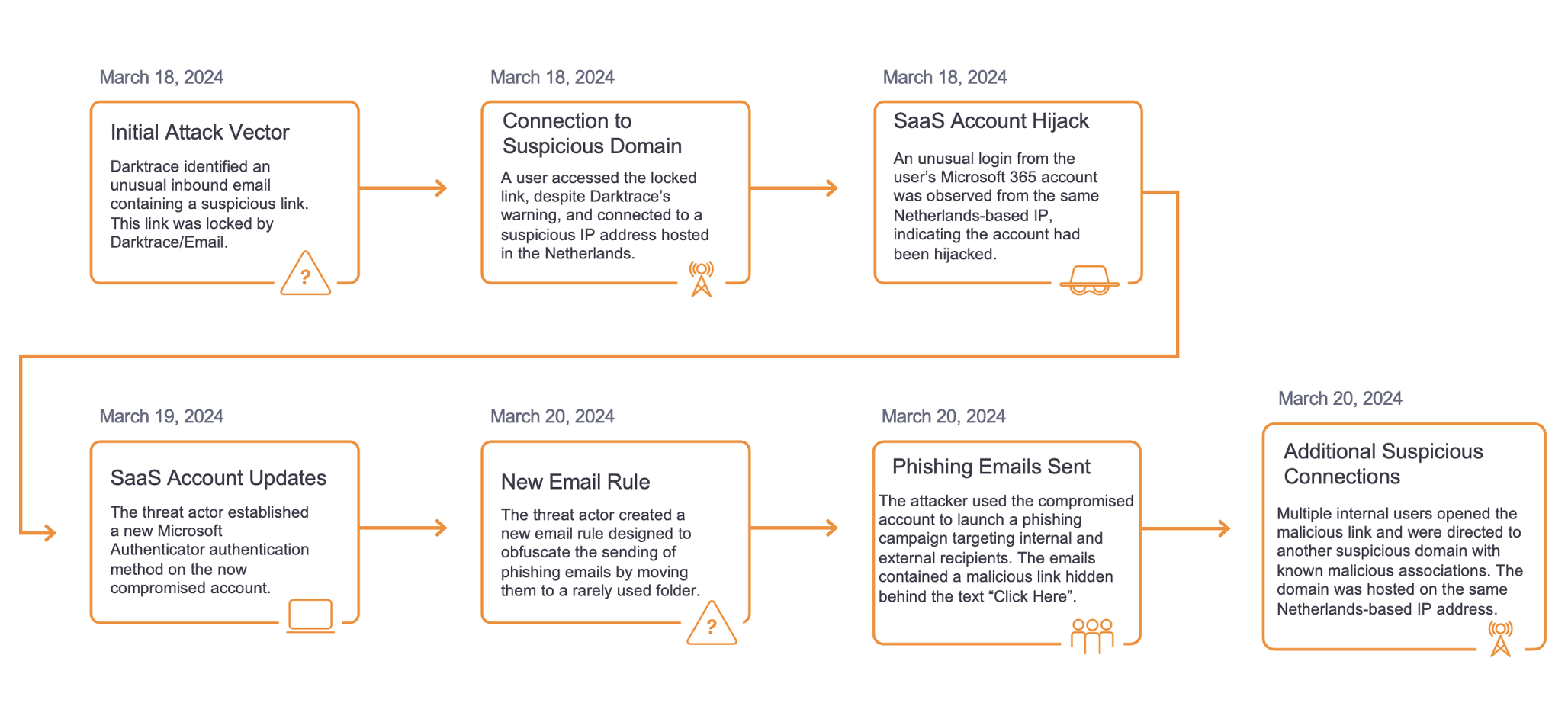

During the month of June, variationsof the following pattern of network activity were observed in several client networks:

1. User’s device contacts an email service such as outlook.office[.]com or mail.google[.]com

2. User’s device makes an HTTP GET request to 185.234.247[.]119 with an Office user-agent string and a ‘/123.RES' target URI. The request is responded to with an HTML file containing a exploit for the Follina vulnerability (CVE-2022-30190)

3. User’s device makes an HTTP GET request with a cURL User-Agent string and a target URI ending in ‘.dat’ to an unusual external endpoint. The request is responded to with a Qakbot DLL sample

4. User’s device contacts Qakbot Command and Control servers over ports such as 443, 995, 2222, and 32101

In some cases, only steps 1 and 4 were seen, and in other cases, only steps 1, 3, and 4 were seen. The different variations of the pattern correspond to different Qakbot delivery methods.

Qakbot is known to be delivered via malicious email attachments [7]. The Qakbot infections observed across Darktrace’s client base during June were likely initiated through HTML smuggling — a method which consists in embedding malicious code into HTML attachments. Based on open-source reporting [8]-[14] and on observed patterns of network traffic, we assess with moderate to high confidence that the Qakbot infections observed across Darktrace’s client base during June 2022 were initiated via one of the following three methods:

- User opens HTML attachment which drops a ZIP file on their device. ZIP file contains a LNK file, which when opened, causes the user's device to make an external HTTP GET request with a cURL User-Agent string and a '.dat' target URI. If successful, the HTTP GET request is responded to with a Qakbot DLL.

- User opens HTML attachment which drops a ZIP file on their device. ZIP file contains a docx file, which when opened, causes the user's device to make an HTTP GET request to 185.234.247[.]119 with an Office user-agent string and a ‘/123.RES' target URI. If successful, the HTTP GET request is responded to with an HTML file containing a Follina exploit. The Follina exploit causes the user's device to make an external HTTP GET with a '.dat' target URI. If successful, the HTTP GET request is responded to with a Qakbot DL.

- User opens HTML attachment which drops a ZIP file on their device. ZIP file contains a Qakbot DLL and a LNK file, which when opened, causes the DLL to run.

The usage of these delivery methods illustrate how threat actors are adopting to a post-macro world [4], with their malware delivery techniques shifting from usage of macros-embedding Office documents to usage of container files, Windows Shortcut (LNK) files, and exploits for novel vulnerabilities.

The Qakbot infections observed across Darktrace’s client base did not only vary in terms of their delivery methods — they also differed in terms of their follow-up activities. In some cases, no follow-up activities were observed. In other cases, however, actors were seen leveraging Qakbot to exfiltrate data and to deliver follow-up payloads such as Cobalt Strike and Dark VNC. These follow-up activities were likely preparation for the deployment of ransomware. Darktrace’s early detection of Qakbot activity within client environments enabled security teams to take actions which likely prevented the deployment of ransomware.

Darktrace Coverage

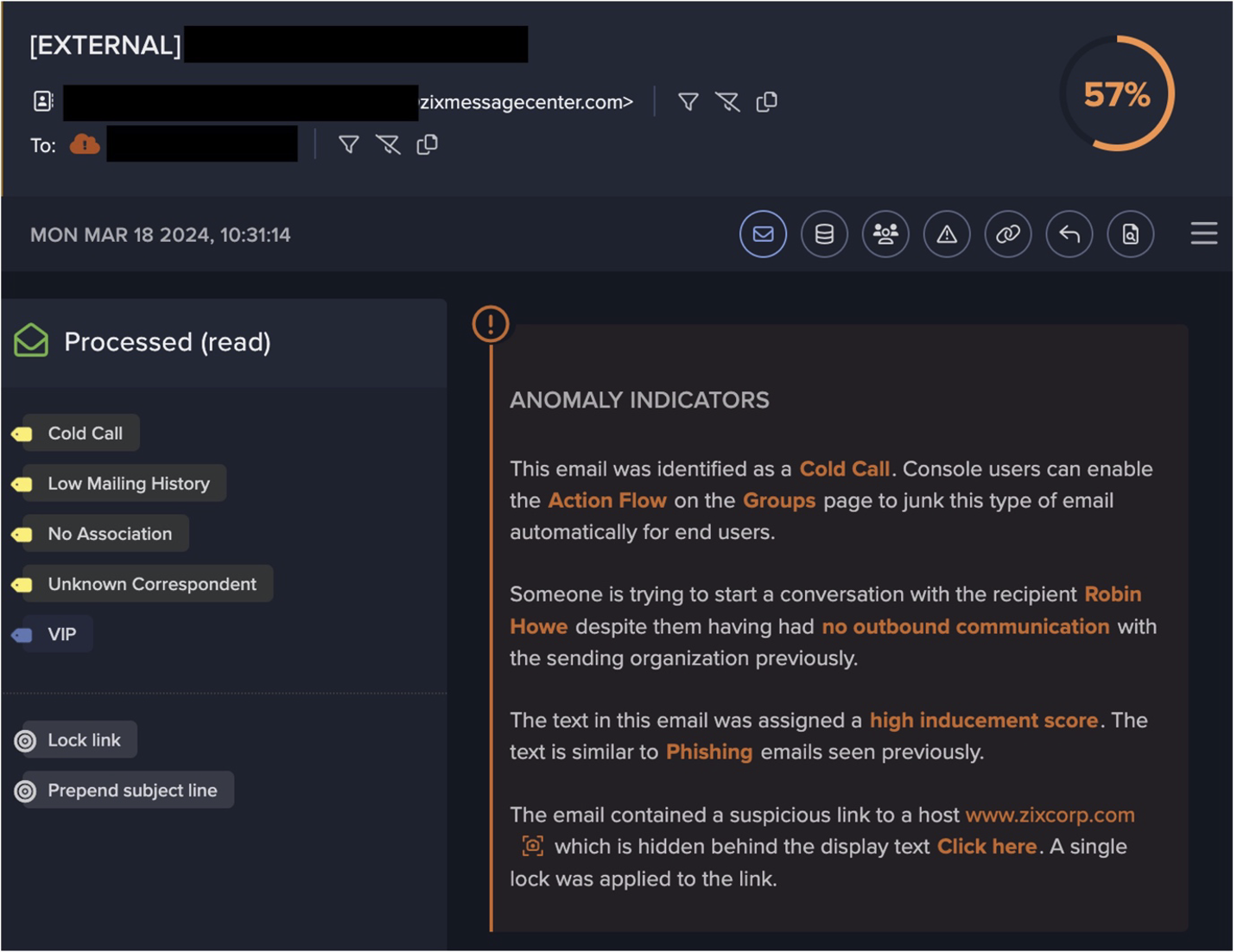

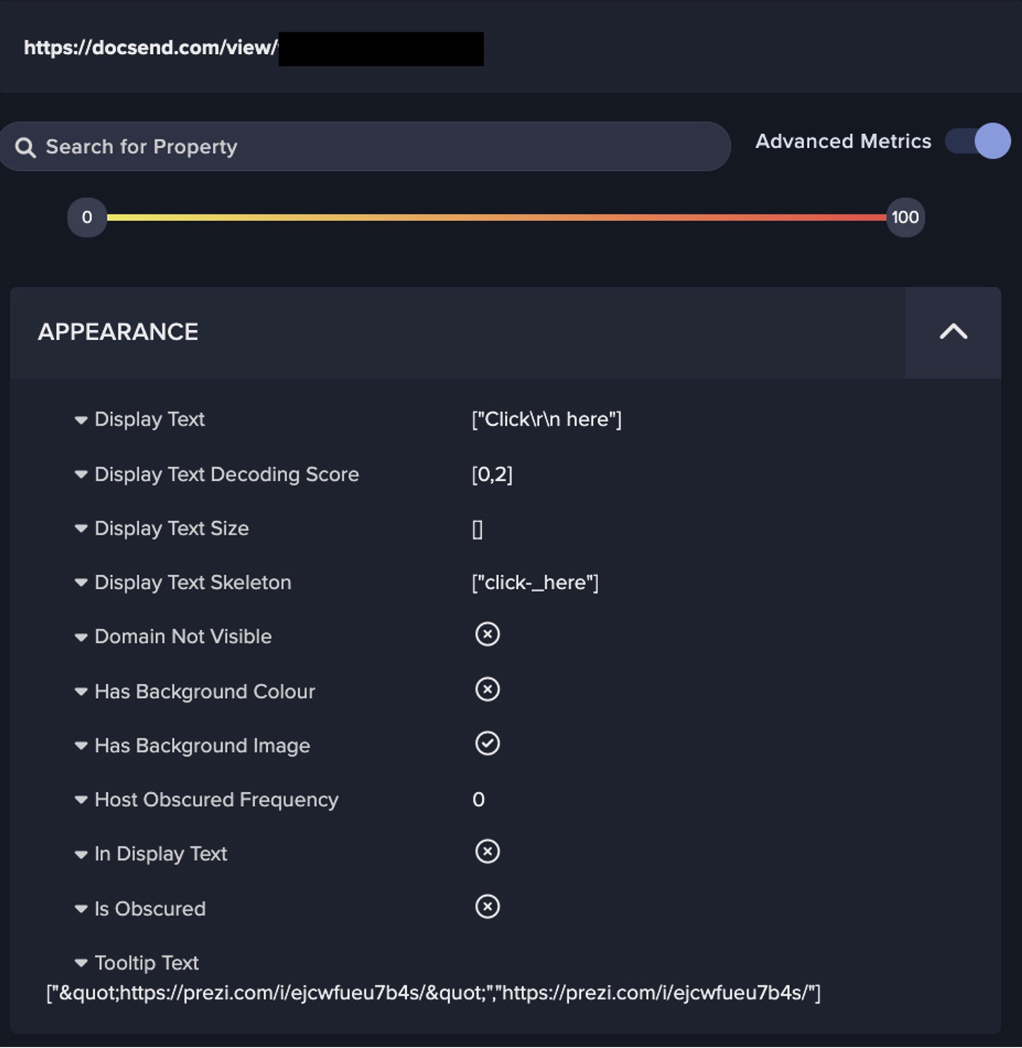

Users’ interactions with malicious email attachments typically resulted in their devices making cURL HTTP GET requests with empty Host headers and target URIs ending in ‘.dat’ (such as as ‘/24736.dat’ and ‘/noFindThem.dat’) to rare, external endpoints. In cases where the Follina vulnerability is believed to have been exploited, users’ devices were seen making HTTP GET requests to 185.234.247[.]119 with a Microsoft Office User-Agent string before making cURL HTTP GET requests. The following Darktrace DETECT/Network models typically breached as a result of these HTTP activities:

- Device / New User Agent

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

- Device / New User Agent and New IP

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / Numeric Exe Download

These DETECT models were able to capture the unusual usage of Office and cURL User-Agent strings on affected devices, as well as the downloads of the Qakbot DLL from rare external endpoints. These models look for unusual activity that falls outside a device’s usual pattern of behavior rather than for activity involving User-Agent strings, URIs, files, and external IPs which are known to be malicious.

When enabled, Darktrace RESPOND/Network autonomously intervened, taking actions such as ‘Enforce group pattern of life’ and ‘Block connections’ to quickly intercept connections to Qakbot infrastructure.

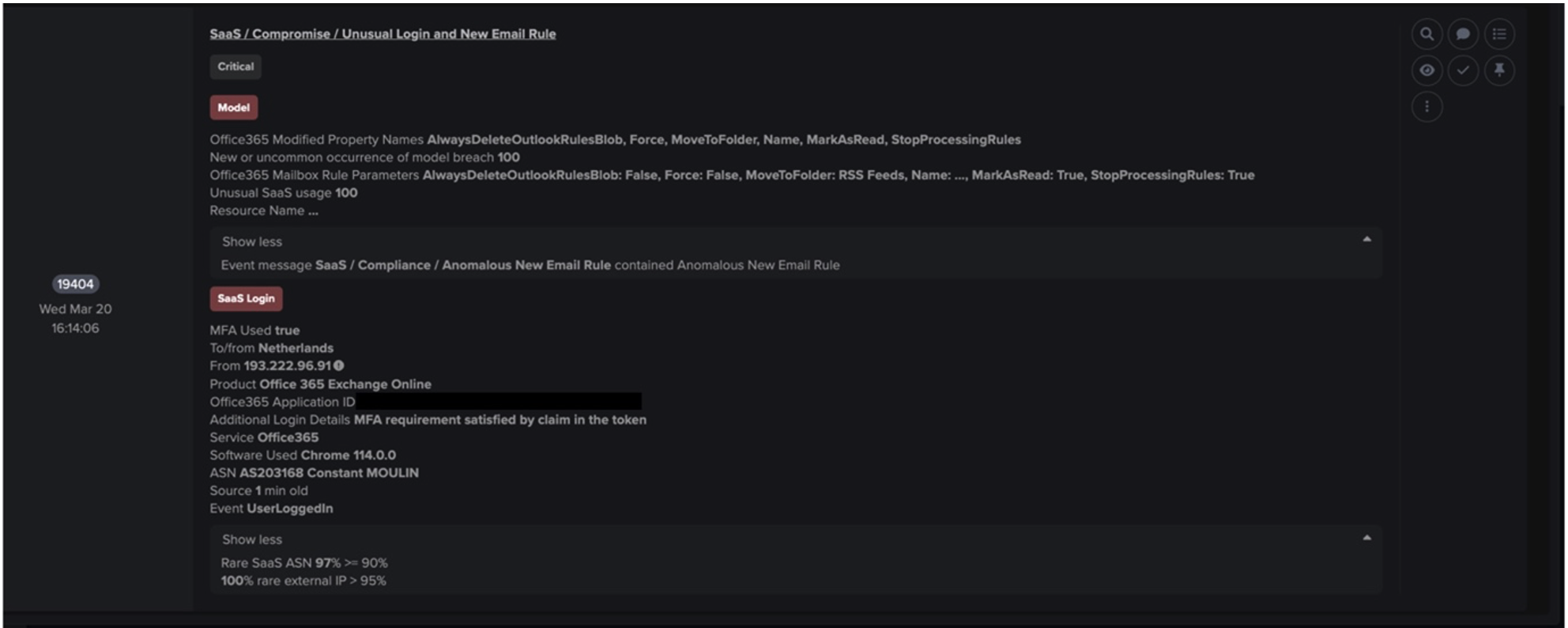

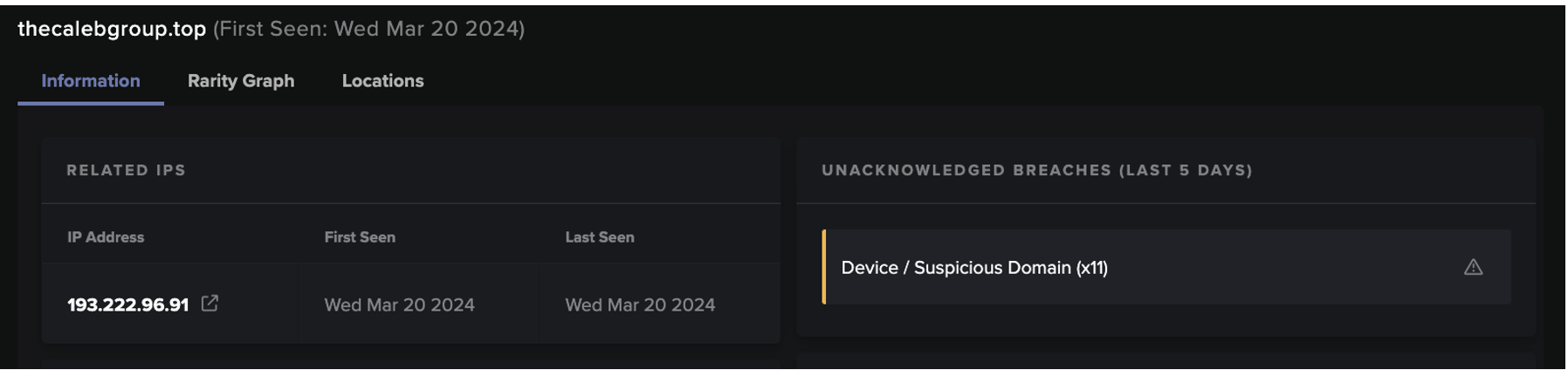

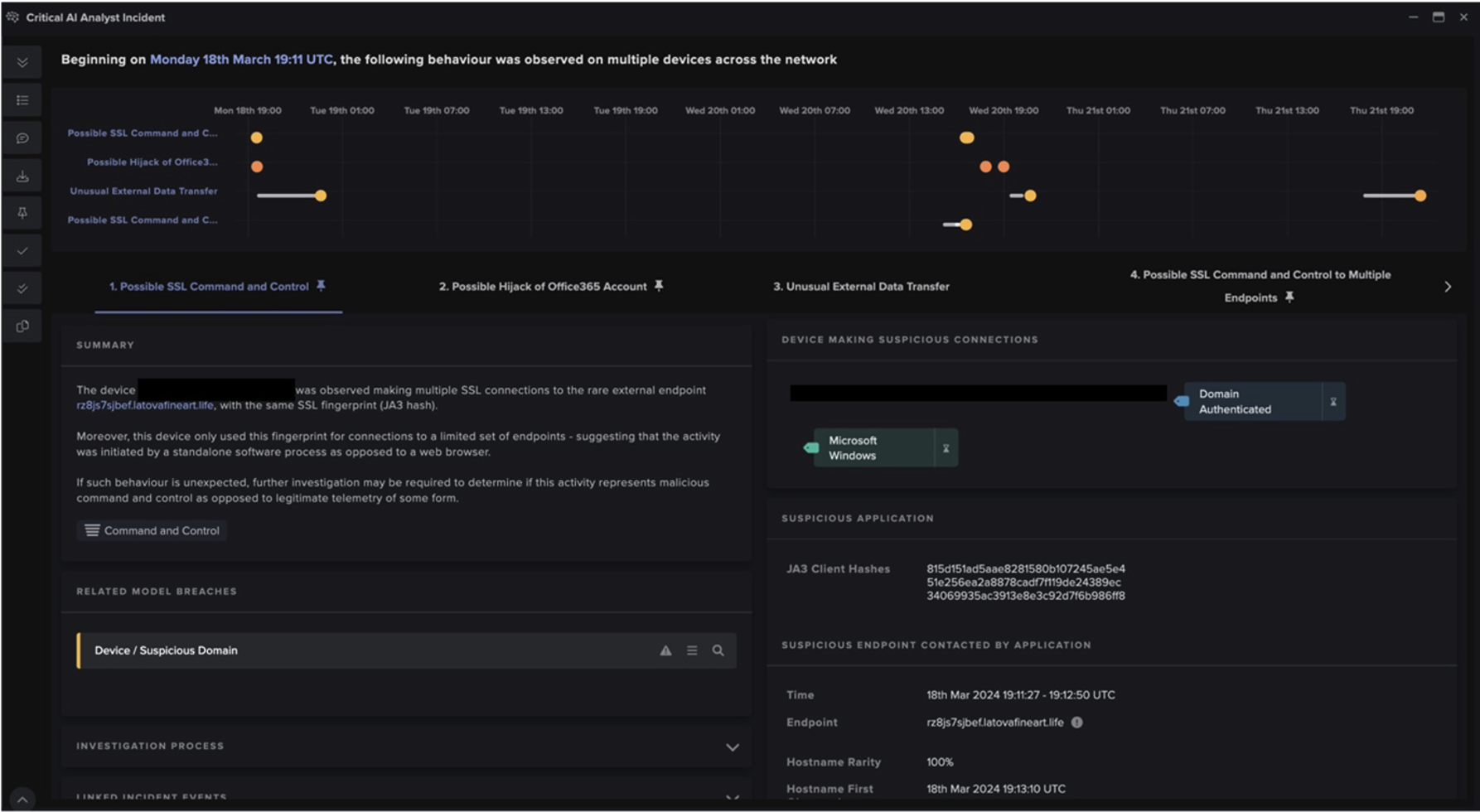

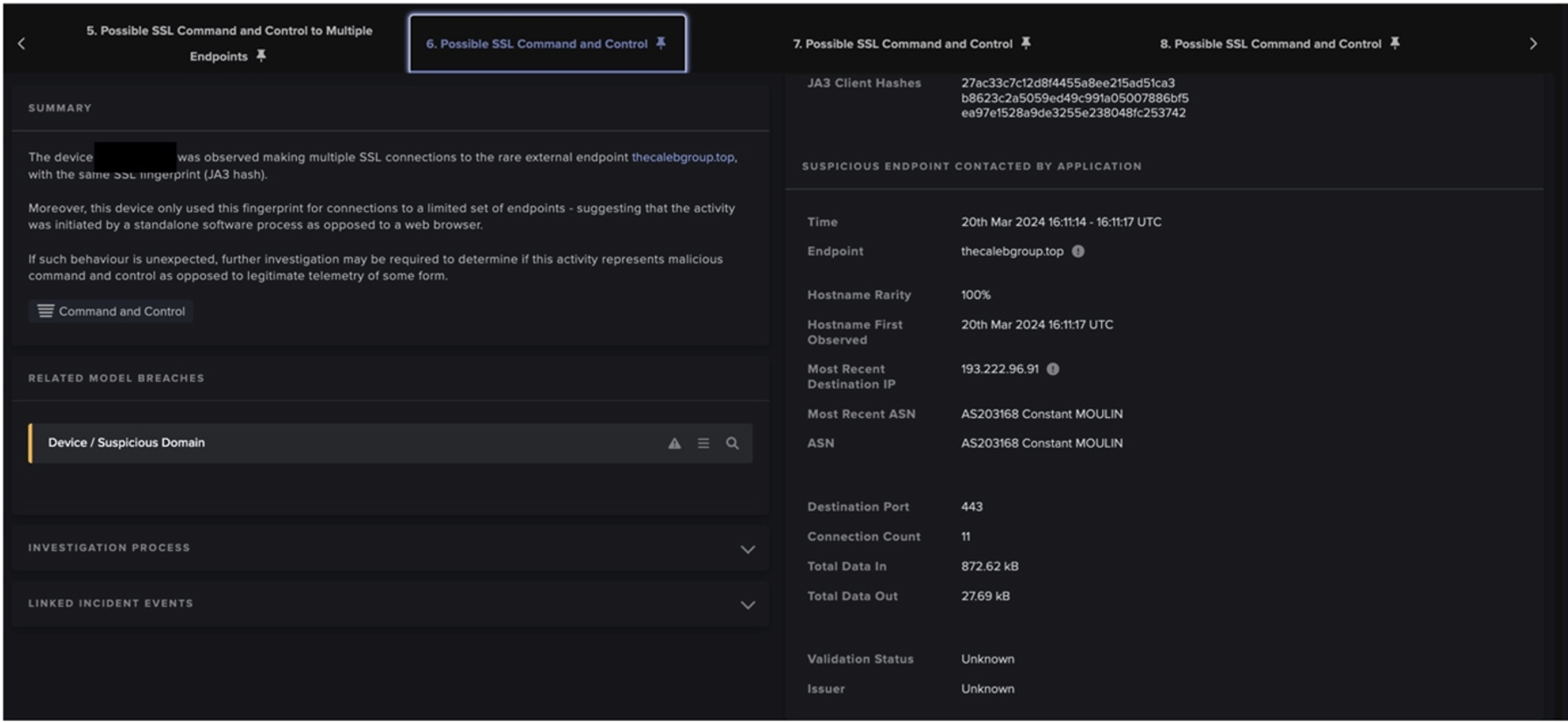

After installing Qakbot, users’ devices started making connections to Command and Control (C2) endpoints over ports such as 443, 22, 990, 995, 1194, 2222, 2078, 32101. Cobalt Strike and Dark VNC may have been delivered over some of these C2 connections, as evidenced by subsequent connections to endpoints associated with Cobalt Strike and Dark VNC. These C2 activities typically caused the following Darktrace DETECT/Network models to breach:

- Anomalous Connection / Application Protocol on Uncommon Port

- Anomalous Connection / Multiple Connections to New External TCP Port

- Compromise / Suspicious Beaconing Behavior

- Anomalous Connection / Multiple Failed Connections to Rare Endpoint

- Compromise / Large Number of Suspicious Successful Connections

- Compromise / Sustained SSL or HTTP Increase

- Compromise / SSL or HTTP Beacon

- Anomalous Connection / Rare External SSL Self-Signed

- Anomalous Connection / Anomalous SSL without SNI to New External

- Compromise / SSL Beaconing to Rare Destination

- Compromise / Suspicious TLS Beaconing To Rare External

- Compromise / Slow Beaconing Activity To External Rare

The Darktrace DETECT/Network models which detected these C2 activities do not look for devices making connections to known, malicious endpoints. Rather, they look for devices deviating from their ordinary patterns of activity, making connections to external endpoints which internal devices do not usually connect to, over ports which devices do not normally connect over.

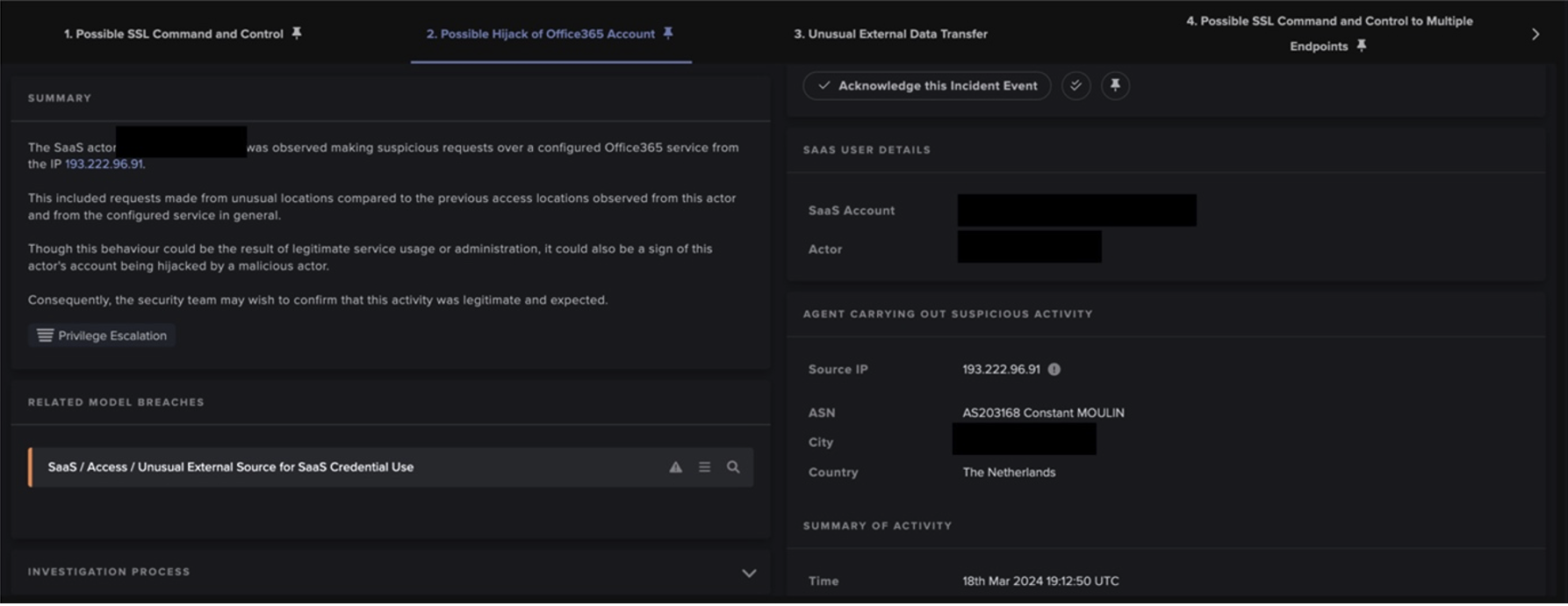

In some cases, actors were seen exfiltrating data from Qakbot-infected systems and dropping Cobalt Strike in order to conduct extensive discovery. These exfiltration activities typically caused the following models to breach:

- Anomalous Connection / Data Sent to Rare Domain

- Unusual Activity / Enhanced Unusual External Data Transfer

- Anomalous Connection / Uncommon 1 GiB Outbound

- Anomalous Connection / Low and Slow Exfiltration to IP

- Unusual Activity / Unusual External Data to New Endpoints

The reconnaissance and brute-force activities carried out by actors typically resulted in breaches of the following models:

- Device / ICMP Address Scan

- Device / Network Scan

- Anomalous Connection / SMB Enumeration

- Device / New or Uncommon WMI Activity

- Unusual Activity / Possible RPC Recon Activity

- Device / Possible SMB/NTLM Reconnaissance

- Device / SMB Lateral Movement

- Device / Increase in New RPC Services

- Device / Spike in LDAP Activity

- Device / Possible SMB/NTLM Brute Force

- Device / SMB Session Brute Force (Non-Admin)

- Device / SMB Session Brute Force (Admin)

- Device / Anomalous NTLM Brute Force

Conclusion

June 2022 saw Qakbot swiftly mould itself in response to Microsoft's default blocking of macros and the public disclosure of the Follina vulnerability. The evolution of the threat landscape in the first half of 2022 caused Qakbot to undergo changes in its delivery methods, shifting from delivery via macros-based methods to delivery via HTML smuggling methods. The effectiveness of these novel delivery methods where highlighted in Darktrace's client base, where large volumes of Qakbot infections were seen during June 2022. Leveraging Self-Learning AI, Darktrace DETECT/Network was able to detect the unusual network behaviors which inevitably resulted from these novel Qakbot infections. Given that the actors behind these Qakbot infections were likely seeking to deploy ransomware, these detections, along with Darktrace RESPOND/Network’s autonomous interventions, ultimately helped to protect affected Darktrace clients from significant business disruption.

Appendices

List of IOCs

.png)

.png)

.png)

References

[1] https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/excel-blog/excel-4-0-xlm-macros-now-restricted-by-default-for-customer/ba-p/3057905

[2] https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/microsoft-365-blog/helping-users-stay-safe-blocking-internet-macros-by-default-in/ba-p/3071805

[3] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/deployoffice/security/internet-macros-blocked

[4] https://www.proofpoint.com/uk/blog/threat-insight/how-threat-actors-are-adapting-post-macro-world

[5] https://twitter.com/nao_sec/status/1530196847679401984

[6] https://www.microsoft.com/security/blog/2021/12/09/a-closer-look-at-qakbots-latest-building-blocks-and-how-to-knock-them-down/

[7] https://www.zscaler.com/blogs/security-research/rise-qakbot-attacks-traced-evolving-threat-techniques

[8] https://www.esentire.com/blog/resurgence-in-qakbot-malware-activity

[9] https://www.fortinet.com/blog/threat-research/new-variant-of-qakbot-spread-by-phishing-emails

[10] https://twitter.com/pr0xylife/status/1539320429281615872

[11] https://twitter.com/max_mal_/status/1534220832242819072

[12] https://twitter.com/1zrr4h/status/1534259727059787783?lang=en

[13] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/rss/28728

[14] https://www.fortiguard.com/threat-signal-report/4616/qakbot-delivered-through-cve-2022-30190-follina

Credit to: Hanah Darley, Cambridge Analyst Team Lead and Head of Threat Research and Sam Lister, Senior Cyber Analyst